What impact could changes to Capital Gains Tax have on your finances?

The billion-pound Government response to the challenges of the pandemic is a debt that will need to be repaid, and a review of the UK tax system suggests change is likely. How could this manifest and what does this mean for your financial planning?

2020 is proving to be a costly year in terms of public finances. The UK Government's commitment to support workers, businesses and the NHS in order to mitigate the consequences of COVID-19 and the steps taken to reduce its spread have seen borrowing rise to unprecedented levels. The Office for Budget Responsibility estimates the figure will hit GBP300 billion in the financial year 2020/21. When set against pre-COVID expectations of around GBP55 billion, that's a big rise.

At some point, of course, that deficit will need to be addressed. Broadly speaking, the Government has three options: cut spending, increase borrowing or raise funds through taxation. Of these, raising taxation is considered most probable, as appetite and political capital for the other two options is likely to be low. As far as taxation goes, the 2019 Conservative Manifesto contained a triple-lock pledge not to increase Income Tax, National Insurance or VAT during the current parliamentary term. That means that other areas of taxation will be open to consideration.

The indications are that the Chancellor has CGT reform in his sights.

CGT in the spotlight

The Chancellor's request to the Office for Tax Simplification back in July to review the Capital Gains Tax (CGT) regime for individuals, partnerships and estates and smaller businesses – combined with the recent press coverage of possible increases – indicates a change to the current CGT seems to be more than a remote possibility, but is it a foregone conclusion?

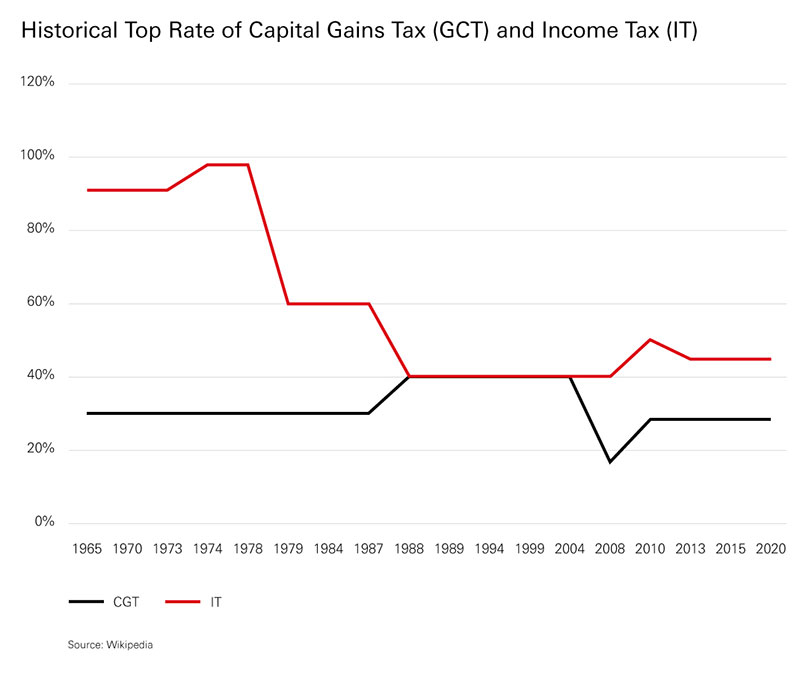

CGT was first introduced in 1965, and covered the gains made on the disposal of assets by individuals, personal representatives and trustees. From 1988, gains were taxed according to Income Tax rates up to a maximum of 40 per cent, before a flat rate of 18 per cent was introduced in 2008, and the higher rate of 28 per cent added in 2010. Other changes, such as Taper Relief, indexation and other reliefs have featured along the way.

So, what areas of CGT may be subject to reform under the current circumstances?

- Rate increase – CGT rates are very low, so it isn't inconceivable that they could be increased, either to align them with Income Tax (as per the recent speculation in the press) or possibly to a higher flat rate than at present.

- Different treatment depending on source – gains from certain sources could be subject to different treatment. For example, increasing the rate at which financial gains are taxed relative to other assets or taxing gains on investment properties as Income Tax rather than CGT.

- Withdrawal of allowances for certain taxpayers, possibly those subject to Additional Rate Tax.

- Introduction of an exit tax for those relocating overseas.

- Change in treatment after death – a loss in the step-up in base cost on death is potentially significant in light of possible future increases in Inheritance Tax.

- Timing changes – currently tax due on gains on the sale of real estate is due 30 days after completion. Bringing tax due on gains on the sale of financial assets in line with this could bring forward tax receipts but could increase complexity in terms of the netting off of gains or losses on a tax year.

- Widening the scope – CGT would thus be based on situs of assets rather than the residence of the owner. This already applies to UK residential dwellings.